Posts Tagged ‘Julian Onderdonk Biography’

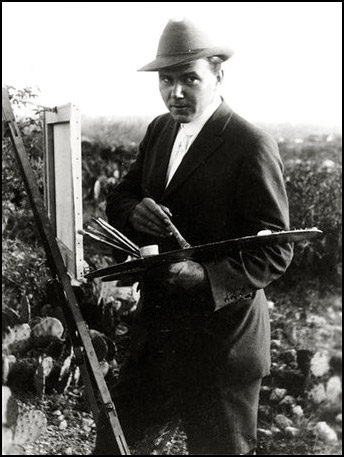

Julian Onderdonk – The Shooting Star of San Antonio

Julian Onderdonk

An Illustrated Biography

by Jeffrey Morseburg

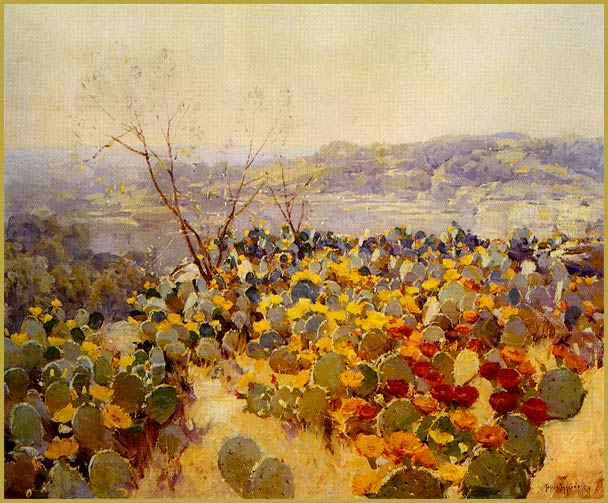

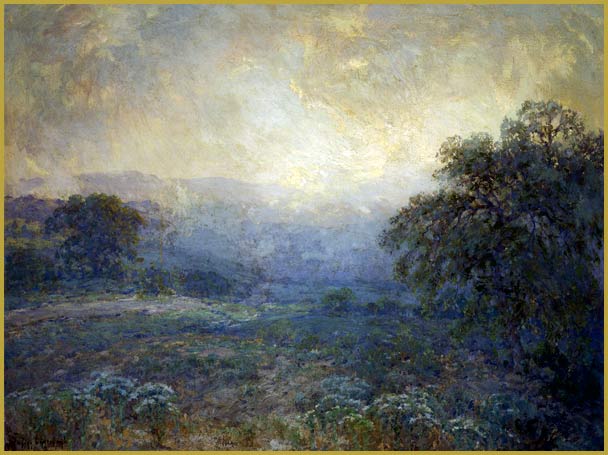

During his short life, Robert Julian Onderdonk was described as “Texas’ Greatest Artist.” He is now referred to as “The Texas Old Master” and remains the most famous and best loved of Texas landscape painters. Through the exhibition of his paintings and the sale of reproductions of his works to visitors to San Antonio, Julian Onderdonk made the beauty of Texas known to Americans who had never visited the Lone Star State. His paintings of fields in the Hill Country of central Texas, awash in sunshine, carpeted with brilliant Bluebonnets, became a legend in his native region. In fact, according to the great folklorist J. Frank Dobie, Onderdonk’s impressionistic and highly atmospheric depictions of wildflowers helped to make Texans themselves more appreciative of the beauty of their state flower. Of course, Julian Onderdonk was much more than simply a painter of spring fauna. He also painted the rolling hills, live oak and cacti of central Texas, usually seen under the intense summer sun, as well as the red oaks as they changed color to a brilliant red under the crisp fall chill and the rustic ranches and Spanish Missions of the vast state.

Robert Julian Onderdonk (1882-1922), who was always known as “Julian,” was the son of a successful artist, Robert Jenkins Onderdonk (1852-1917), often described as “The Dean of Texas Painters.” He was born in San Antonio, Texas on June 30, 1882. His father, who was of Dutch descent, had been born in Maryland and grew up in a family of scholars. The elder Onderdonk studied art in New York at the National Academy and then as one of the first students at the Art Student’s League. He came to Texas in 1879 to paint portraits for a year and never left. He met his wife, Emily Wesley Gould Onderdonk (1860-1928), a native of Rhode Island, in San Antonio and they married in April of 1881.

Robert and Emily Onderdonk settled into married life in the Monte Vista section of San Antonio, which was then the largest city in the state. Three children were born to the coupleover the next five years, first Julian, then Eleanor Rogers Onderdonk (1884-1964) and finally Latrobe Henry Onderdonk (1887-1957). Robert Onderdonk was an exceptional painter and his academic training allowed him to tackle almost any subject he set his mind to. His versatility was important in a state that was just emerging from the frontier era and where there was a limited market for fine art. However, for a time Robert Onderdonk struggled in San Antonio and moved to Dallas, where he taught and painted portraits between 1889 and 1896, when his father-in-law’s death precipitated a move back to San Antonio. He painted landscapes, still lifes and a number of the most famous scenes of Texas history including The Fall of the Alamo, which showed the last stand of the Texans at the old mission and The Surrender of Santa Ana.

Young Julian Onderdonk grew up surrounded by paintings, drawings and art books and seemed to always know that he would be a painter. Family legend has it that he began his artistic career by sketching on the butcher’s paper that the family dinner was wrapped in. Some of early newspaper accounts claimed that the senior Onderdonk discouraged his son’s interest in art, but the facts don’t seem to support this. In fact, Julian’s first studies were with his father. He was always drawn to the landscape and as a boy of fourteen he would leave the family’s home under the laurel trees on French Place in San Antonio and trek to the historic San Juan Mission, where he would sketch. In 1898, when Onderdonk went away to attend the West Texas Military Academy, his father critiqued his work via letters and by the time he graduated in 1899, his technique had improved. In 1901, when he was nineteen, the aspiring artist took his savings and money he borrowed from the banker G. Bedell Moore, who was a family friend, and departed for New York to further his artistic career.

Once there, Onderdonk enrolled in classes at the famous Art Students League, where his father had studied a generation earlier. He first took classes from the academic painter and muralist Kenyon Cox (1856-1919). Cox, who was a student of the French master Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904), believed in a highly structured course of study, based on the principles of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, which began with rigorous studies of plaster casts of classical sculpture. Onderdonk, who was an active and impatient young man, chafed at the degree of rigor instructors like Cox and his next teacher, the figurative painter Frank Vincent DuMond (1865-1911), demanded because he wanted to rush forward into painting.

In the spring of 1901 Onderdonk saw works by the American Impressionist William Merritt Chase (1849-1916) exhibited at the National Academy of Design and was impressed by their bold color and vigorous brushwork. Chase, who was something of an artistic guru, had been one of his father’s teachers early in his career and the young Texas artist decided that he wanted to study with him as well. Chase was one of the nation’s most distinguished painters. He was sophisticated, well fed, witty and warm, and also something of an artistic entrepreneur. Chase helped to create the type of commercial artist’s workshops that we know today. Each summer he taught out door classes for aspiring artists, where he painted for his students and critiqued their work. While Chase’s outdoor classes had their share of hobbyists, there were also ambitious young painters like Onderdonk, and his father encouraged him to attend the summer school. The student wrote his parents that “I am very glad that you want me to go to the summer school for I was crazy to go for I feel I could do better there than in a blamed old cast room….I long to get out in the open air with my palette in one hand and my brush in the other and be able to smear paint over the whole landscape.”

So, in the summer of 1901, Onderdonk attended Chases’s summer classes in Shinnecock, Long Island, which would change the course of the young painter’s life and career. Chase was a proponent of “alla-prima” painting, the process of working on a small landscape or figurative painting while it was wet, producing a painting from start to finish in a single sitting. In his Plein-air classes, Chase emphasized capturing the overall impression of what the artist saw before him rather than getting caught up in extraneous detail. Under Chase’s experienced eye, Onderdonk rapidly discovered his destiny as a landscape painter. Onderdonk loved working in the field, painting the scene nature put before him, bathed in natural light and alive with atmosphere. The young artist’s work improved rapidly and his early pieces were modest in size, but beautifully observed, always painted with quick, confident daubs of the brush. On Onderdonk’s birthday on June 30, Chase honored him by painting his portrait as a demonstration for the class. The artist’s family later donated the beautifully executed painting, which was done in Chase’s inimitable style, to the Witte Museum in San Antonio.

After a summer and autumn of painting outdoors, Onderdonk worked under the academic instructor Frank Vincent DuMond during the winter term, but it had become apparent to him that he didn’t want to continue with formal studies in order to pursue a career in portraiture and historical scenes as his father had. As an artist who felt most at home painting in nature, he decided that his career would be dedicated to the landscape. His last formal instruction was an evening class with Robert Henri (1865-1929), the Realist painter and legendary teacher. Out on his own, Onderdonk began to support himself by selling small landscapes that he had painted on location. Most of these early works were atmospheric woodland scenes that were done in a limited palette. When looking at these small Onderdonks, the thing that is most interesting is that they are painted as if the late George Inness was looking over the artist’s shoulder, not his mentor William Merritt Chase. Like most exceptional painters, Onderdonk was highly observant – when he admired an artist’s work like he did that of Inness, it came out on the canvas, albeit through the prism of his own unique artistic sensibility. The canvases and panels from his early years were painted in a bold, confident, manner like those of Chase but they sang with the poetic sensibility and simplicity that is characteristic of Inness, who was a Tonalist. This writer would even argue that Onderdonk’s later Texas works retain the soft touch and air of mystery of Inness, the man who was considered the finest American landscape painter at the turn of the century.

In New York, Onderdonk met a young woman named Gertrude Shipman (1886-?) who was four years his junior. The relationship progressed rapidly and on June 19, 1902 the young couple were married. In 1903, a daughter, Adrienne, was born. In New York, with the pressures of supporting a family now thrust upon him, Onderdonk fortunately began to experience some success. In 1903, one of his works was accepted for the prestigious Society of American Artists exhibition and the following year he sent one of his paintings to Dallas, where the newly formed Dallas Art Association purchased it. In the summer of 1904, he made a brief foray into teaching summer classes and opened the Onderdonk School of Art, but his stab at instructing was not a success, perhaps because his name was not yet a big enough draw.

Despite the rapid progress Onderdonk had made in the east, he yearned to return home to Texas. In 1906 he was hired to select the paintings for the annual exhibition at the Texas State Fair, which was held in Dallas each October, a task his father had been given previously. This was a tremendous vote of confidence in the taste and judgment of an artist who was only twenty-four. Initially, this job allowed him to travel from New York to Texas to supervise the installation of the paintings, but he saw this curatorial job as an opportunity. His salary could not only fund his family’s move back to San Antonio, but once there, the stipend from the fair would allow him time to establish himself as a painter. Once he was home, the task of organizing the art for the annual fair would mean trips to New York each summer to select the paintings, allowing him to socialize with the friends and to make contacts with people on the art scene. However, curating the exhibits for the fair would also involve a great deal of tedious work organizing the shipment of the art and cataloging the paintings. The San Antonio Light wrote the sale of Robert Jenkins Onderdonk’s “The Brass Bowl” at the Texas State Fair in October of 1907 and noted that Julian “…has only one painting on exhibition here, it being a spring time afternoon. Mr. Onderdonk made the selection of paintings for the Dallas Art Association and was so modest that he sent but one of his own.”

In 1909 Onderdonk had a modest exhibtion of his Plein-air works at the Rice Gallery in New York titled Thumb Nail Sketches, but by this time he and his wife, who was pregnant with their second child, must have had their mind on their long awaited move to Texas. The Onderdonks arrived in San Antonio on November 14, 1909. Because they could not afford a place of their own, they moved in with his family, which made the Onderdonk home and studio on French Place even more crowded and busy than it was already. At the Onderdonk home there was now Julian, his new wife Gertrude, their young daughter Adrienne Onderdonk (1903-1963) and soon a son, Robert Reid Onderdonk (1909-1963), who would be born that December. There was also Julian’s mother and father, his artistic younger sister Eleanor, brother Latrobe and also his mother’s brother Stephen, three of his children and finally a pair of servants – some fourteen in all. A decade later, there would still be ten residents living under the roof of the house that Emily’s father had built in 1882, one which would remain a beehive of activity until the 1940s.

“Bluebonnets at Late Afternoon” Oil on Canvas, 10″ x 14″ (1915)

San Antonio Museum of Art

The three artists in the Onderdonk family – Robert, Julian and Eleanor, who was becoming a painter in her own right – had to share a rustic studio building on their French Place property that had plenty of good, northern light. It was filled with shelves for artist’s materials, a large collection of books and the props that Robert Onderdonk used in his historical works. The studio was also used for private lessons, which were then as now a way for prominent artists to augment the income they made from selling paintings Once he had established himself as a major talent in Texas art, Julian Onderdonk was also a sought out as a teacher. While he did take on a few students, he did not teach extensively, perhaps because his curatorial duties for the fair were already enough of a distraction from his own painting. Soon after his arrival in Texas, Onderdonk celebrated his homecoming by painting one of his rare figurative scenes of his father, mother, sister and wife playing cards, a common evening activity for the family.

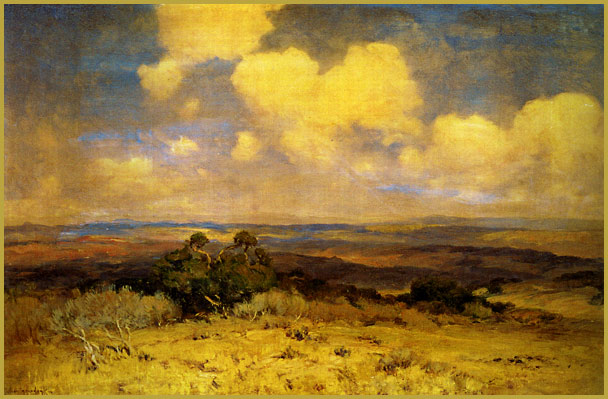

Once home in Texas, Onderdonk soon discovered the subjects that spoke to him as an artist. He was born a Texan and had yearned to use the skills that he had developed in the east to depict his native land. He said that “While I was still studying…it was my one ambition to return to Texas and to paint some of the things that I remembered as a boy….I found, however, that my memory had played me false, for it was like stepping into another world, the wonders of which had been read of, never seen.” Because each region has its own unique light and atmosphere, what Onderdonk was probably writing about was the adjustment in his palette and his technique that was necessary to fully capture the intense southern light of Texas. Because he had grown up in Texas he would have recognized what was lacking in his early attempts at capturing the landscape of the Hill Country. Venturing out to the countryside that surrounded San Antonio, he continued painting small studies on location, but he began to take them back to the studio where they could be worked up into larger and more ambitious landscapes.

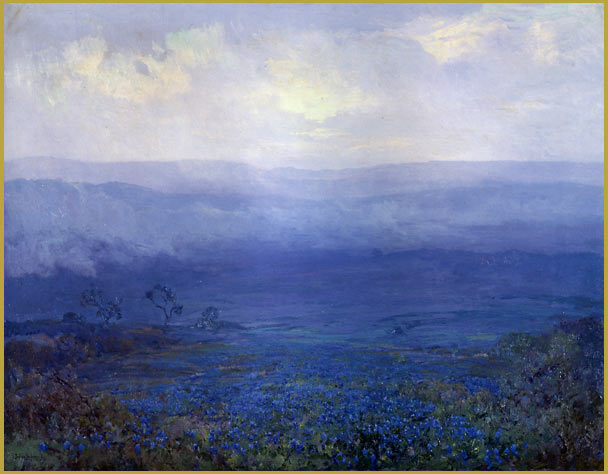

About 1911, Onderdonk discovered the Bluebonnet landscape, the subject he would become best known for. Each spring, a number of varieties of blue lupin blanket the hillsides of the Texas countryside, sometimes by themselves and, on other occasions, mixed in with other wildflowers. In the bluebonnet, the artist found a subject he truly enjoyed painting and we must remember that in those early days of Texas art, before color printing was in widespread use, bluebonnet paintings were not yet the commercial staple they would become. He wrote that, “I like the bluebonnet because a field of this Texas flower seems just to have burst from the ground and it trembles subtly, making it beautiful.” In that quotation the artist identifies what this writer believes made Onderdonk’s paintings of wildflowers stand out – it was the shimmering light, the “vibrative” quality that he achieved through his warm palette and Impressionist technique. Onderdonk’s flowers seem like living things that truly exist in the unique atmosphere in which they were painted – they were not simply broadly painted renditions of a carpet of flowers.

“Bluebonnets in Texas” Oil on Canvas, 42″ x 54″ (c. 1915)

Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum

Where many Eastern artists had little interest in painting the desert with its intense sunshine, lack of dramatic topography and absence of forests and greenery, Onderdonk had a completely different perspective. He wrote that, “San Antonio offers an inexhaustible field for the artist. Nowhere else are the atmospheric effects more varied or more beautiful. One never tires of watching them. Nowhere else is there such a wealth of color. In the spring, when the wildflowers are in bloom, it is riotous: every tint, every hue, every shade is present in the most lavish profusion, and even in the dead of summer when one would imagine that any canvas could only convey the impression of intense heat, the possibilities of the landscape are still beyond comprehension. One has only to see it properly to see that everything glows with a wonderful golden tint that is a delight and the despair of all of us who have ever tried to paint it.”

Onderdonk’s job assembling the work for the Texas State Fair in Dallas was a major responsibility, and after the fair organizers decided to include the work of Western painters as well as the Eastern artists, it became even more time consuming. Fortunately, it also gave him the opportunity to travel east each year to select the paintings that would be exhibited, allowing him to keep current with the trends in the New York art world. While his work as a curator was an important means of support for his family, he began to grow frustrated at how much time it took away from his painting. However demanding it was for Onderdonk, his work in curating the annual exhibition was vital for Texas artists, because exhibition opportunities were scarce and the paintings from the East gave them the opportunity to see the artistic trends that were developing in the art centers of the nation.

Because of the dearth of venues, the major exhibition that Onderdonk was able to participate in each year was the Texas State Fair Exhibition that he curated and his father helped judge. His mature work was first shown there in 1901, while he was still living in the East, and then each year that the exhibition featured Western artists, from 1907 to 1910 and then again in 1913. Onderdonk also sent his work to the new Texas Artists Exhibition in Ft. Worth each year from 1911 through 1914. Although the opportunities to display fine art in Texas were few and far between, the exhibitions that were held were supported well and did draw visitors, so by 1914, Julian Onderdonk was considered his father’s heir-apparent as the dean of Texas painters.

Before the 1920s, the commercial galleries in San Antonio and much of the West often paired the exhibition of paintings with photographic studios. In 1914 and 1915, Onderdonk exhibited his work at the Fred Hummert Picture Gallery in downtown San Antonio. The Bohemian-born photographer and artist Ernst Raba (1874-1951) who was and old friend of Onderdonk’s father, was a major contributor to the cultural life of the “River City.” His studio was a place that the early artists of San Antonio gathered and it often served as an exhibition space. The Carnegie Library in San Antonio, the high school and the churches were also called into service as exhibition spaces. Major annual exhibitions for Texas painters would only start in San Antonio after Onderdonk’s death and the completion of the Witte Museum in 1927. In search of sales and trying to widen his market to collectors outside Texas, he sent paintings north to Chicago, where he exhibited at the gallery in the vast Marshall Field’s Department Store. In 1916 the Palette and Brush Society of San Antonio hosted a solo exhibition for Onderdonk. In May of that same year he packed up his work and sent it to Dallas for his only major solo exhibition to be held outside San Antonio. The Palette and Brush Society also sent a large exhibition of work by San Antonio artists to Houston that spring.

In 1917, Robert Jenkins Onderdonk passed away and his son succeeded him as the torchbearer of Texas art. As he became established, he was asked to serve on committees, present awards, to lecture and to speak at luncheons in San Antonio, Dallas and even as far away as Galveston, on the Gulf Coast. In 1920 he was described in the Galveston paper as “Julian Onderdonk of San Antonio, whose paintings are known to all the art centers of the United States” when he spoke on the need for society to apply artistry to many different areas of life. Onderdonk had another solo exhibition in San Antonio that April that included thirty-one works and was described in the San Antonio Evening News as “…the most complete of its kind ever shown here.” The exhibition included a number of paintings of Bluebonnets, but also wildflower scenes with milkweed, verbena, and coreopsis, paintings of the rivers, oak trees and even a snow scene. By the time he entered his mid-thirties, the modest Onderdonk was considered the man who had helped to popularize the Texas landscape. He copyrighted some of his bluebonnet scenes and reproductions of his paintings were sold to tourists at the historic Joske’s Department Store overlooking the Alamo Plaza in San Antonio.

Like many artists, Onderdonk could be quite hard on himself. He became frustrated with his work and was filled with self-doubt. In 1921 he wrote: “I should enjoy to be able to paint one really good picture, but it seems to get more and more difficult. There was a time when I was vain enough to think I might do this some day but that day draws further in the distance as time goes on. Keep in mind that this was a time when he was already greatly admired and generally acknowledged to be the finest painter in his home state. He was also disappointed to be thought of as the “Bluebonnet Painter” for he didn’t want to be associated with the amateur painters who tackled the same subjects but without his keen eye and graceful handling.

In the fall of 1922, as he was just entering his prime, Onderdonk was rushed to the hospital with an intestinal blockage. He failed to recover from the emergency surgery and died on October 27, 1922. His sudden death created an outpouring of emotion for the man who had become “The Dean of Texas Painters.” Just before he died, Onderdonk had finished a beautiful early morning view of a Texas hillside carpeted with Bluebonnets titled “Dawn in the Hills” and another work, a bold fall scene titled “Autumn Tapestry.” When Onderdonk died, these works were about to be shipped to the National Academy of Design in New York for their annual exhibit. Although the Academy’s regulations state that works in the annual exhibition must be by living painters, Onderdonk’s entries were included in the show because his death took place after the paintings had been accepted, beneath crossed palms and a purple ribbon. A short time after the artist’s death the San Antonio newspapers led a drive which raised funds to purchase “Dawn in the Hills” so that it could be donated to the San Antonio Artist’s League, in recognition of Julian Onderdonk’s tremendous contributions to Texas art.

J. Frank Dobie (1888-1964) was a Texas folklorist, educator and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He was also a writer who wrote about the Texas Bluebonnet and the art it inspired. In his famous essay on the Bluebonnet he wrote about Onderdonk: “A few years later Julian Onderdonk, of San Antoinio, took the breath of the sensitive with his painting of a bluebonnet field. ‘Nature Follows Art.’ Texans have become increasingly conscious of the beauty, the fragrance, and, when seen in mass, the power of the bluebonnets. Seizing upon the flowers popularity, every dauber in the country tries his hand at painting it, and bluebonnet chromes are as plentiful as cowboy figures on pulp magazine covers. Yet no amount of commercialism, no fad running into insipidity, no betrayal in the same of art, can detract from the essential loveliness of the flower springing on the hills and valleys of Texas…”

As a postscript, only a few years after Julian Onderdon’s death, the Witte Museum was opened in San Antonio. It became the major repository of Early Texas Art and the site of exhibitions of both contemporary and historic paintings. The first curator was Julian’s younger sister Eleanor Onderdonk, who never married and kept working at the Witte until city regulations required her to retire in 1957, so the Onderdonk family’s contributions to Texas art continued long after Robert Jenkins and Robert Julian Onderdonk had painted their last Texas landscape. The Witte was also the site of the Texas Wildflower Competitions from 1927 to 1929, which helped reinforce San Antonio’s status as an Art Colony and to make the Bluebonnet landscape a Texas institution. By the 1940s, Bluebonnet painting had become such an institution that Life magazine ran an extensive article on this unique Texas artistic pursuit.

Today, the Witte Museum in Onderdonk’s native San Antonio is the largest repository of his work. Just a few years before this essay was written, the Onderdonk studio was moved from its French Place location to the grounds of the Witte, so those who love his paintings can get some idea of the artist’s own environment. The artist’s large book collection was sold to the oilman and bibliophile Edgar Davis soon after the artist’s death and then donated to the San Antonio Artist’s League. When America’s second Texas President was sworn into office in 2001, the Oval Office was redecorated with Texas art because President George W. Bush wanted to be reminded of home. These works included one work by the aging Tom Lea and no less than three Onderdonk landscapes.

Works by Robert Julian Onderdonk can be found in the National Museum of American Art in Washington D.C., the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington, the Monticello College Foundation in Godfrey, Illinois, the Amon Carter Museum in Ft. Worth, the El Paso Museum of Art, the Dallas Museum of Art, the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library in Austin, Texas, the Stark Museum in Orange, Texas, the Texas Tech Museum of Art in Lubbock, the Jack Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, the Meadows Art Museum in Dallas, the Modern Art Museum of Ft. Worth, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library in San Antonio, the Marion Koogler-McNay Museum, San Antonio, Texas A & M University, the Texas Fine Art Association, the San Antonio Museum of Art and with the San Antonio Art League. Copyright 2010-2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without specific written permission of the author.